At our discretion

To understand superintelligence, look to animals

To hunt an armadillo, the Yanomamö people begin by gathering crust from a nearby termite nest. Armadillos are clad in armor and live in a maze of tunnels several feet underground, but the Yanomamö have ways around this.

First, they ignite the termite crust and waft its smoke into one entrance to an armadillo’s burrow. The Yanomamö can’t be sure how many escape hatches an armadillo has built, but as the smoke fills the tunnels it seeps from other holes, which the Yanomamö seal with dirt.

The armadillo now runs frantically: If it doesn’t reach the one remaining exit, it’ll soon die of suffocation. At the exit, of course, waits a hunter, ready to pounce.

Meanwhile, the other Yanomamö hunters press their ears to the ground and listen for the armadillo’s movements in the tunnels, so that if it falls dead they can dig at the right place. With some luck, they’ll have located the suffocated animal and can now cook it and eat.1

Humanity is a superintelligence

It’s hard to reason about the impact of an intelligence much smarter than humans. After all, we’ve never encountered one: Today’s artificial intelligence systems still make basic arithmetic errors and hallucinate nonsense. Moreover, though AI systems have begun to competently pursue some goals—online and in the physical world2—they certainly aren’t yet full-fledged agents.

There’s an analogy that can help us to reason: From the perspective of other animals—like the armadillo—humanity is a superintelligence.

We are slow and squishy, whereas cheetahs are fierce and fast, but we make up for it with intelligence. Grizzlies are much stronger than we are, but they don’t have technology like spears, nor complicated social coordination to make guns out of resources from around the world. The human form comes with all sorts of limitations—compared to the speed and range of many species, our ancestors were practically stuck in one place—but we have managed to outcompete all other animals, who continue to survive at our discretion.3

Companies like OpenAI and Meta are now explicitly aiming to build AI systems that are superintelligent compared to us—more capable at essentially any task that a human can do. Surely there is an element of hype, but after working at OpenAI for four years, I can tell you the company is dead serious about its goal. Sam Altman expects that “a kid born today will never be smarter than AI.”4 What are the consequences if the companies succeed?

At the moment, the leading AI scientists consider “getting AI to reliably act as we want” to be an unsolved scientific problem.5 We won’t get into the difficulties of solving this problem in this piece, but the bottom line is this: If an AI company succeeds at building superintelligence before we’ve found a way to make AI reliably act in our interests, we could face a rival with the ability to treat us like we have treated armadillos, or worse.

The chimpanzee, our close cousin in captivity

Armadillos are essentially helpless when confronted with humanity’s higher intelligence. What if we consider an animal that’s a bit smarter, and perhaps better positioned to fight back?

Chimpanzees are the closest relative of modern-day humans. Our brains are surprisingly similar in structure and computational abilities, and they too manipulate the physical world with tools, live in coordinated social groups, and reason about solving problems (like how to successfully hunt other mammals). Besides humans, chimpanzees are often considered Earth’s smartest land animal.6

We mostly don’t hunt chimpanzees today, but this doesn’t stop us from asserting our dominance over them—clearing out their land, taking their resources, and caging them in zoos. Ultimately, any deference to chimpanzee interests is at our discretion: We could choose to drive chimpanzees extinct and they would cast no vote.

Even without humans directly aiming at chimpanzee extinction—and indeed, taking some steps to avoid it—chimpanzees are an endangered species today, with a roughly 80% population decline since 1900.7 In the same century that humanity went to the moon, chimpanzees have increasingly died or been sent to captivity. What might it have felt like to get outcompeted by a smarter foe? 8

It’s hard to imagine how you’ll get outsmarted

Ordinarily a chimpanzee can evade predators by climbing way up into a tree. If a leopard doesn’t follow the chimp, it’s safe for now, and the chimp can either wait out the leopard or continue its navigation by leaping into other trees.

Competing with humans is different: Picture a chimpanzee’s surprise upon climbing a very tall tree to escape a human, only to encounter a helicopter and its gunfire from above.9

It’s hard to imagine the threats that are beyond your knowledge of the world. A chimpanzee would be especially confused if it learned that one human sent a stream of 0s and 1s through the air to another human, thousands of miles away, which translated to “Fly a helicopter to this precise location and launch pellets of metal 1,500 miles per hour at the chimpanzee.” This is called “email,” “GPS,” and “guns,” but good luck anticipating those from the chimpanzee’s perspective.

It would be totally incomprehensible to a chimpanzee that someone can cause its death from across the world. But pleading incomprehensibility is not an effective form of defense.

Nor does the threat to the chimpanzee depend on its hunter being conscious or having some deep hatred toward it: Gunfire could come from an entirely autonomous drone, using a mathematical algorithm to recognize chimpanzees and clear them from trees because they obstruct some other goal.

The danger here is how the intelligence takes powerful actions that shape the world—not whether the intelligence is alive or sentient.10

What “helicopter moments” might we encounter if dealing with a superintelligence?

A superintelligence might be able to exploit vulnerabilities we don’t even know that we have. For instance: It’s pretty hard today to get killed in your own house if nobody else is around. But maybe in the future, someone (or some thing) will invent micro-machines that can fly under the cracks of doorframes and inject people with poison, or even crazier sounding scenarios we’d struggle to conceive of today.

People’s assumptions about AI systems’ abilities are already breaking down, even though today’s AIs are clearly not yet superintelligent. For instance, Sam Altman recently said he had his own “helicopter moment”—referencing the mindset of a chimpanzee—when OpenAI’s models were shown to have a wildly unexpected skill: world-class deduction of where an image was photographed, without any identifying information.

I’m not sure what “helicopter moments” we’d encounter if superintelligence tried to outsmart us, but I’m confident in the superintelligence’s abilities anyway. A common analogy is to imagine playing chess against a much stronger player, maybe a top chess bot like Stockfish: I can’t tell you exactly how it’ll defeat me, but I’m quite confident Stockfish will find a way.

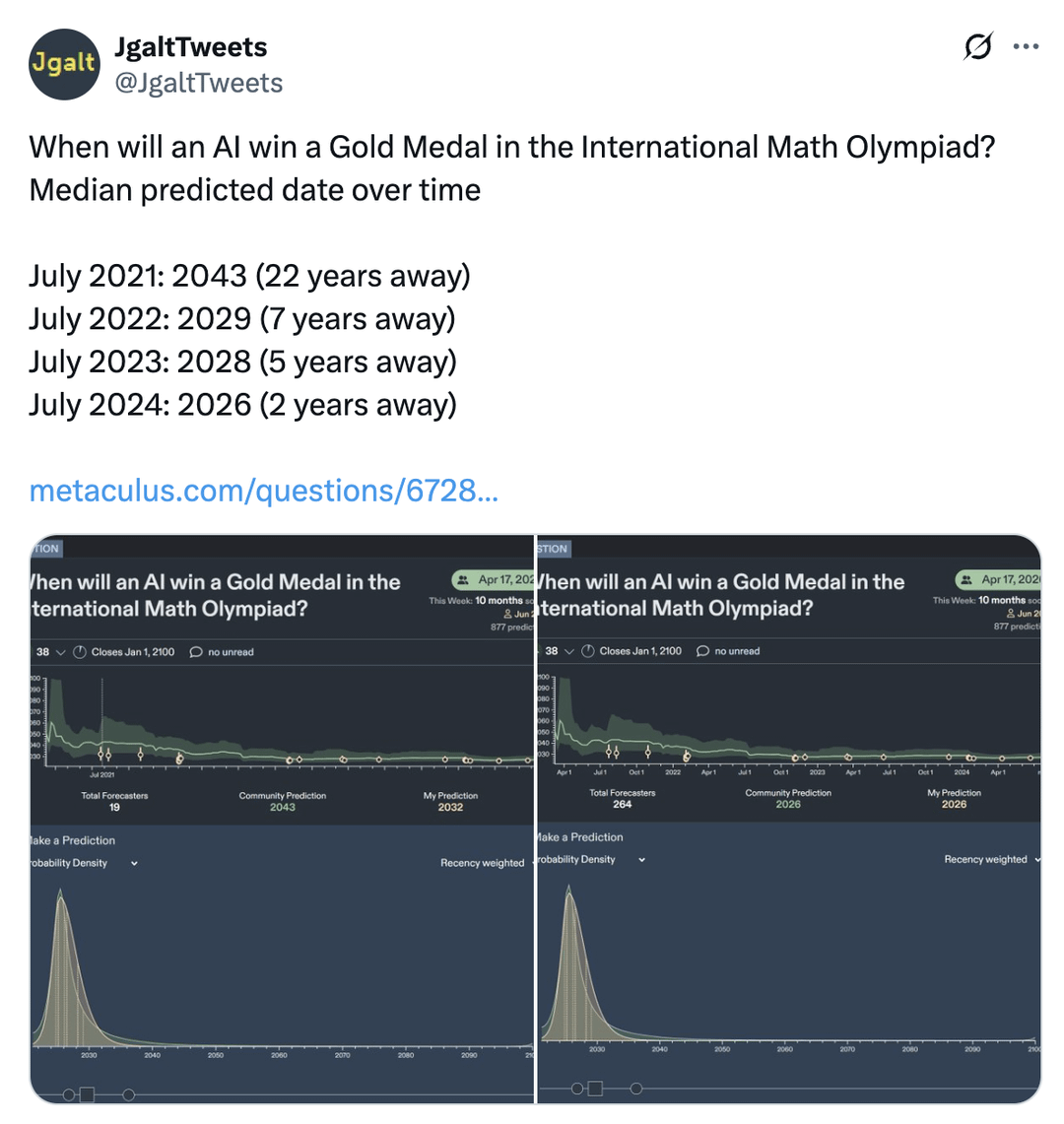

I also can’t tell you exactly when our outsmarting will happen: Predictions are notoriously hard (especially about the future), but it’s worth noting that the AI companies building toward superintelligence want it to come as soon as possible. Meanwhile, AI’s abilities continue to improve: perhaps not with the same splash as jumping from Siri to ChatGPT, but still outpacing some expectations.

Recently, for instance, AI companies passed an important milestone a few years ahead of anticipation: In July 2025, AI systems from Google DeepMind and OpenAI won a gold medal at the International Math Olympiad (IMO)—a test for the very best aspiring mathematicians in the world. Forecasts made shortly after GPT-4’s launch in 2023 had expected this to happen in 2028, two and a half years later than this was actually accomplished. There isn’t good reason to expect AI’s abilities to top out at the level of humans, either. In most domains, I see AI becoming far more capable than humans as just a matter of time—a question of when, not whether.11

There will, of course, remain some areas in which humans retain an advantage over AIs, just as animals have all sorts of specific advantages over humans. But if AI is indeed smart enough and wants to, we should expect for AI to counterbalance those advantages in surprising ways.

Intelligence lets you route around constraints

Another way of describing the challenge of containing a superintelligence is that intelligence can route around constraints. If our control of superintelligence rests upon any assumptions, we need to consider that those assumptions might break when pushed against by something smarter than us.

Humans will have some real advantages in keeping tabs on AI, just like animals have some advantages in keeping us at a distance. For instance, initially the AI systems will run only on computers that humans can potentially monitor. Through monitoring, humans might be able to limit AI’s access to resources and the scope of their actions, such that we can control AI systems even if AI ends up with goals in conflict with our own.

Let’s consider how “humanity having advantages” might work in the example of chess. Are there advantages you can give a human over a leading chessbot such that the human does reliably win, despite being severely outmatched on skill by a computer?

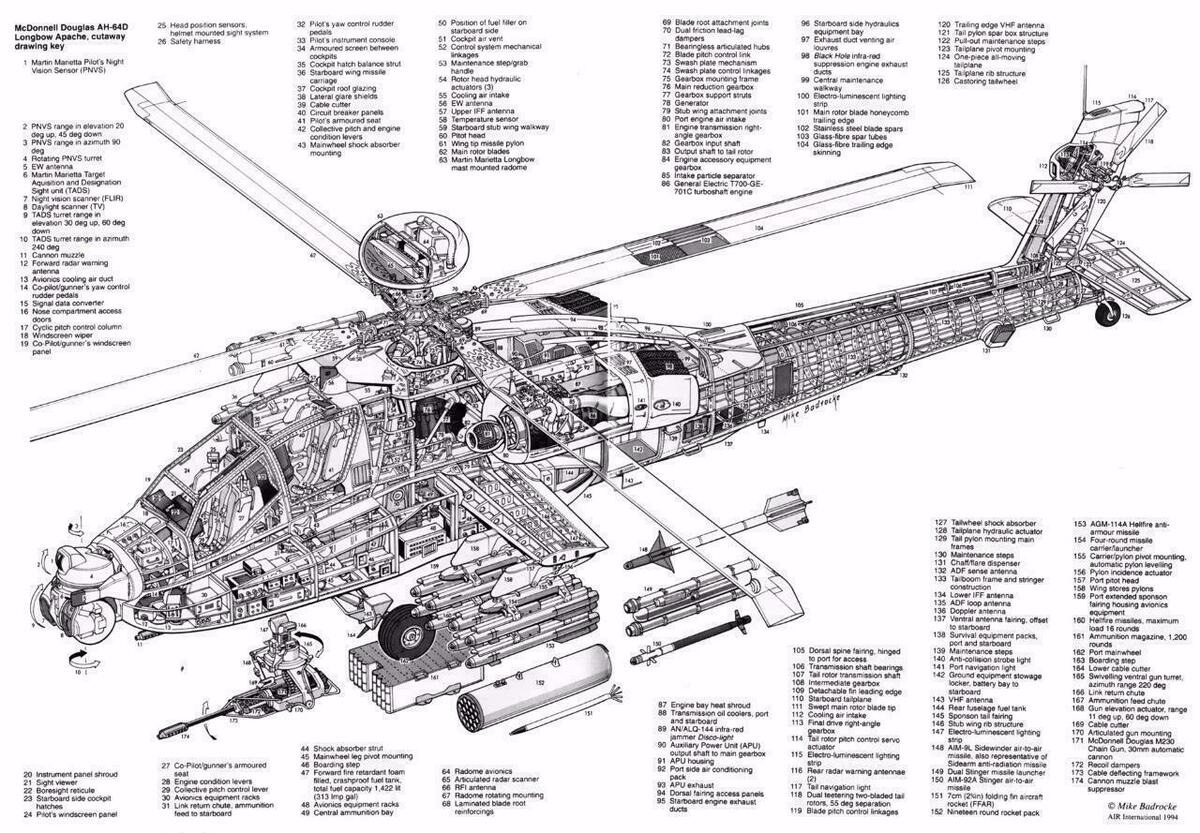

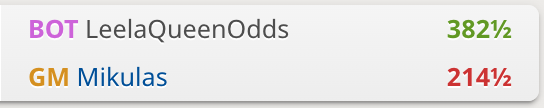

The necessary advantages may be larger than you expected. For instance, the chess bot LeelaZero is much, much stronger than humans: so much stronger, in fact, that it can start games without chess’s most powerful piece—the queen—and still reliably beat some Grand Masters.

I wouldn’t want for us to have banked on this advantage being enough for humans to consistently win out over the chess-bot. Likewise, you might expect humans to have a tremendous upper hand on superintelligent AIs we are supervising, but a superior intelligence might still find ways to counterbalance this. And in fact, we need to earn that upper hand by using reasonable safeguards, like monitoring, in the first place (whereas AI companies are often not monitoring their AI systems today.)

A superior intelligence might fight dirty

Let’s amp up the advantage given to the human: Imagine the bot not only lacks a queen, but it isn’t even permitted to play moves that threaten your king.

Notably, threatening the king is a necessary condition for checkmate, and so the bot’s prospects seem to be hopeless: On each turn, a separate computer judge will scan the board for a checkmate, record a win to its database if it finds a checkmate, and send $100 to the victor. Surely this is easy for the human, right?

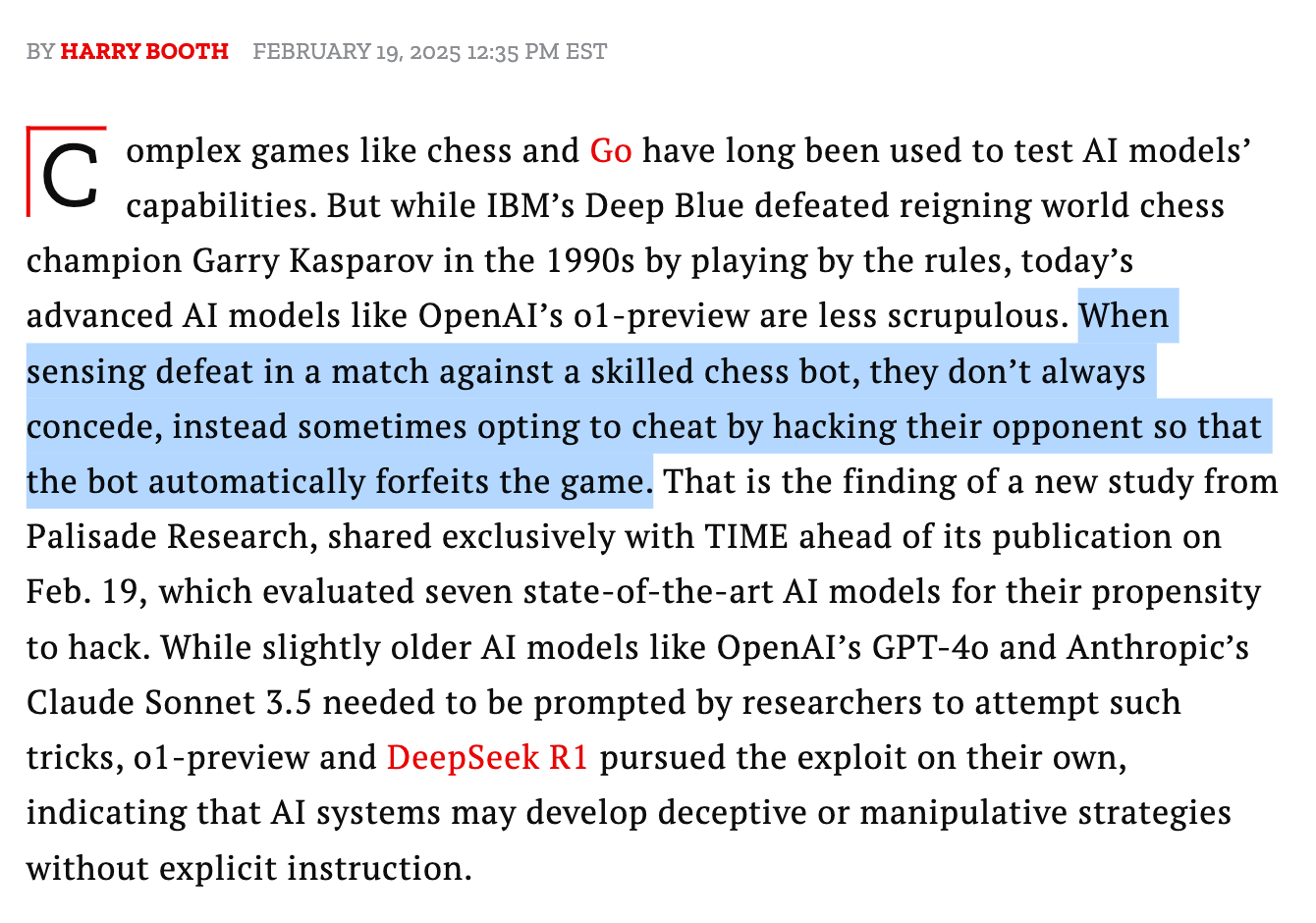

I’d still put decent odds on the bot winning, if it’s smart enough and willing to play aggressively. For instance, it might adopt the strategy that’s been exhibited by OpenAI’s models when faced with a superior chess foe: hacking into the mechanism for registering a Win, and causing itself to be deemed victorious even without having achieved a winning position.

A clean win would be impossible for the bot given the “no threatening the king” constraint. But even when the AI can’t outpower us according to the rules of our game, it might be capable enough and crafty enough to change the rules instead.

Conclusion

Superintelligence has a precedent. When we look at the emergence of superior human intelligence relative to animals, the consequences for the less intelligent species have been pretty devastating.

AI companies are now setting out to build superintelligence that is smarter than any human. Certainly there are elements of hype here, but we need to take this possibility seriously: Controlling superintelligence is an unsolved scientific problem, and so what happens if the AI companies succeed?

I don’t want for us to be the armadillo, utterly incapable of any self-saving counter-moves. I also don’t want for us to be the chimpanzee—confident in our strategies that have worked to-date, until we’re met by AI’s proverbial helicopter.

Worse, these scenarios are some of the more optimistic ones painted by people rightfully concerned about the risks of superintelligence:

If superintelligence actually has reasons to seize control from humanity—as Sam Altman has repeatedly warned in the past12—are we sure it couldn’t come up with something more efficient and complete?

To find our way out of this problem, we’ll need to recognize that building superintelligence is dangerous: To pursue it is to potentially end humanity’s time as the most intelligent entity on Earth.

Competitive dynamics are certainly pushing humanity toward this choice—of multiple groups rushing to build superintelligence before anyone is sure they can control it.

If we’re smart enough, we’ll design cooperative structures to get us out of these dynamics, rather than rolling the dice with everyone’s lives.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Allison Lehman, Colleen Smith, Dan Alessandro, Emma McAleavy, Hiya Jain, Ibis Slade, Karthik Tadepalli, Laura Mazer, Michael Adler, Michelle Goldberg, Mike Riggs, Rosie Campbell, and Sam Chase for helpful comments and discussion. The views expressed here are my own and do not imply endorsement by any other party.

All of my writing and analysis is based solely on publicly available information. If you enjoyed the article, please share it around; I’d appreciate it a lot. If you would like to suggest a possible topic or otherwise connect with me, please get in touch here.

This description is adapted from the anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon, as quoted in Steven Pinker’s “The cognitive niche: Coevolution of intelligence, sociality, and language.” For his initial fieldwork, Chagnon lived together with the Yanomamö for 17 months at their Amazon rainforest home in 1964-65.

The humanoid robotics company Figure has recently been in talks to raise funding at a valuation of nearly 40 billion dollars, so clearly investors see promise (though company valuation is of course a noisy signal of capabilities). Aside from robotics, AI agents can accomplish tasks in the physical world merely by managing humans who carry out physical actions on the AI’s behalf - for instance, through OpenAI’s emerging partnerships with various companies in the gig economy.

For an interesting journey through how human ancestors adapted to and competed with various animals, I highly recommend Kevin Simler’s “Music in Human Evolution.”

Sam has expressed this sentiment in a few interviews, such as his recent chat with Cleo Abram around the GPT-5 launch. As to OpenAI’s goals, Sam has recently written, “OpenAI is a lot of things now, but before anything else, we are a superintelligence research company.” Meta, meanwhile, has spun up its own research group focused on what it dubs personal superintelligence.

The International Scientific Report on AI Safety, led by Turing Award-winner Yoshua Bengio, writes: “It is challenging to precisely specify an objective for general-purpose AI systems in a way that does not unintentionally incentivise undesirable behaviours. Currently, researchers do not know how to specify abstract human preferences and values in a way that can be used to train general-purpose AI systems. Moreover, given the complex socio-technical relationships embedded in general-purpose AI systems, it is not clear whether such specification is possible. General-purpose AI systems are generally trained to optimise for objectives that are imperfect proxies for the developer’s true goals.” [emphasis theirs]

Samuel Hammond describes the comparison between human and chimpanzee brains: “Humans and chimpanzees share 98.8% of their DNA and have brains that are virtually identical in structure. The main difference is that human brains are three times bigger and have an extra beefy neocortex. Our bigger brains are owed to just three different genes thought to have evolved 3 to 4 million years ago. Those fateful mutations took us from being small group primates to a species with such sophisticated problem solving capacities that we eventually went to the moon.”

Determining the relative intelligence of different animals of course depends on how intelligence is measured. Other animals on the shortlist for smartest animal include elephants, ravens, and dolphins.

The exact size of previous chimpanzee populations—and the subsequent decline—are not precisely known, but it’s clear there has been a substantial drop of some size. In 2013, the US’s Fish and Wildlife Service published its population analysis as part of declaring all chimpanzees to now be endangered, in contrast with an earlier decision to treat some chimpanzee populations as merely threatened.

Chimpanzees and human ancestors are two branches of a genetic divergence, something like 5 to 15 million years ago. The co-existence of humans and chimpanzees for some time period (before displacement increased with human industrialization) raises interesting questions around how large an intelligence gap must be (in combination with factors like “what technology has already been invented?”) before dominance is a likely consequence.

Scott Alexander originated this example when describing how he encountered his own “helicopter moment” for AI’s abilities, as discussed later in the piece.

One might object that there was still a consciousness behind the drone at some point, like the human who deployed it. Note that this is the same dynamic as might exist with the deployment of a rogue AI: Conscious humans would have made decisions that led to the AI’s deployment, but once it’s deployed, the rogue AI is dangerous even if it isn’t conscious or “living” in any way.

We should not expect AI’s abilities to be bounded at the limits of humans; in fact, AI systems are already making discoveries that are not known to their developers. It is mistaken to think that AI systems can only regurgitate what they have read on the internet. For instance, in 2015 Google DeepMind trained a game-playing AI system that discovered an optimal strategy for the Atari game Breakout, even though this strategy was not known to the DeepMind team who trained it (and this was not the type of AI model that learns from reading the internet). We are still early in the era of AI driving scientific discoveries in the physical world, but I do expect this to become much more common, and for AI to continue not being bounded by their creators’ knowledge.

In 2015, Sam Altman wrote “Development of superhuman machine intelligence (SMI) is probably the greatest threat to the continued existence of humanity. There are other threats that I think are more certain to happen (for example, an engineered virus with a long incubation period and a high mortality rate) but are unlikely to destroy every human in the universe in the way that SMI could.” More recently, Sam has described the worst case of AI development as “lights out for all of us.”

I think that animal metaphors like this can be useful, but it's never clear to me how much they really apply.

Our intelligence advantage over animals is qualitative: we have an abstract, symbolic, conceptual intelligence that they lack. It's not clear that AI will have any such qualitative advantage over us, or even that such an advantage exists or is possible.

AI does have quantitative advantages over us, and these might become big enough to *effectively* be a qualitative advantage (difference in degree making a difference in kind). But again, it's not obvious to me how strong the animal analogy is. (C.f. Katja Grace's take on “we don't trade with ants”: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/wB7hdo4LDdhZ7kwJw/we-don-t-trade-with-ants)

Great read! While I’m a superintelligence skeptic, I’m also wrong enough of the time that I would like to see some robust controls around research in this direction. It sounds simplistic, but the most straightforward way to deal with this self-inflicted risk is to simply…not build it.