Mythbusting the supposed "1,000+ AI state bills that would hobble innovation"

40% of the bills barely mention AI at all

People keep saying that US states have proposed 1,000+ AI-related bills this year.

This statistic has been at the center of a major Congressional fight in the “Big Beautiful Bill”: whether to strip individual states of their ability to regulate AI, via a 10-year moratorium on state AI regulation.1

Here’s the issue: The claim about the supposed 1,000+ state AI bills doesn’t hold up to analysis, nor does the implication that the bills would hobble innovation.

I dug into the supposed “1,000+” state AI bills directly, as well as reviewed third-party analysis. Here’s what I found:

Roughly 40% of these supposed bills don’t seem to really be about AI.

Roughly 90% of the truly AI-related bills still don’t seem to impose specific requirements on AI developers. (Sometimes these laws even boost the AI industry.)

More generally, roughly 80% of proposed state bills don’t become actual law, and so quoting the headline number of bills is always going to overstate the amount of regulation.

All things considered, what’s the right headline figure? For frontier AI development, I would be surprised if more than 40 or so proposed state AI bills matter in a given year, the vast majority of which won’t become actual law.2 If these laws would in fact contradict each other, I would like for critics to note these contradictions more directly, rather than implying it via the alleged number of proposed bills.

Who’s making the argument about the supposed 1,000+ AI bills?

Many prominent groups and individuals have repeated this claim of the supposed 1000+ AI-related state bills proposed this year.

Their basic argument is that, without Congress passing a moratorium on state AI regulation, there will be a complicated patchwork of state AI laws. After all (the argument goes), states have already proposed more than 1,000 AI bills this year: This amount of legislation would be onerous to comply with and perhaps even contradictory across states. As a consequence, the US might miss out on innovation or even fall behind China on AI competition.

Here are some examples of groups claiming this 1,000+ number, generally without justifying it or providing original sourcing:

A filing from the US Chamber of Commerce.

A senior lawyer at OpenAI claiming it at a retreat for leaders in digital policy.

The CEO of a pro-technology trade association (TechNet: “Tech's most powerful advocacy group.”) repeating the claim in an Op-Ed calling for Congress to pass the moratorium.

Wall Street Journal coverage of the Congressional debate.

Clearly the “1,000+ state AI bills” claim is a powerful meme. But is it actually correct, and what implications should we draw from it?

Roughly 40% of the supposed 1,000+ bills aren’t even really about AI

Let’s look at the bills3: Roughly 40% just aren’t about AI in any significant sense—for instance, in my analysis, I find that they never say “artificial intelligence” or “AI” anywhere in the bill, or they say it only once.4

Here’s an example of one such bill, which happens to be the very first in the list of the “1,000+”, Alabama’s House Bill 169.

Is Alabama’s House Bill 169 actually an AI-related bill, in the sense that counting it is relevant for deciding whether we need a moratorium on state AI regulation?

Pretty clearly not: House Bill 169 is a very standard bill to fund public universities and K-12 education in the state of Alabama. As far as I can tell, this bill is counted as AI-related among the 1,000 bills because it says “artificial intelligence” exactly once, when granting $125K of Alabama’s 5.5 billion dollar public education budget (0.002%).5

Of course, keyword analysis can only get you so far; it’s important to analyze the conceptual content, even if specific words aren’t said.

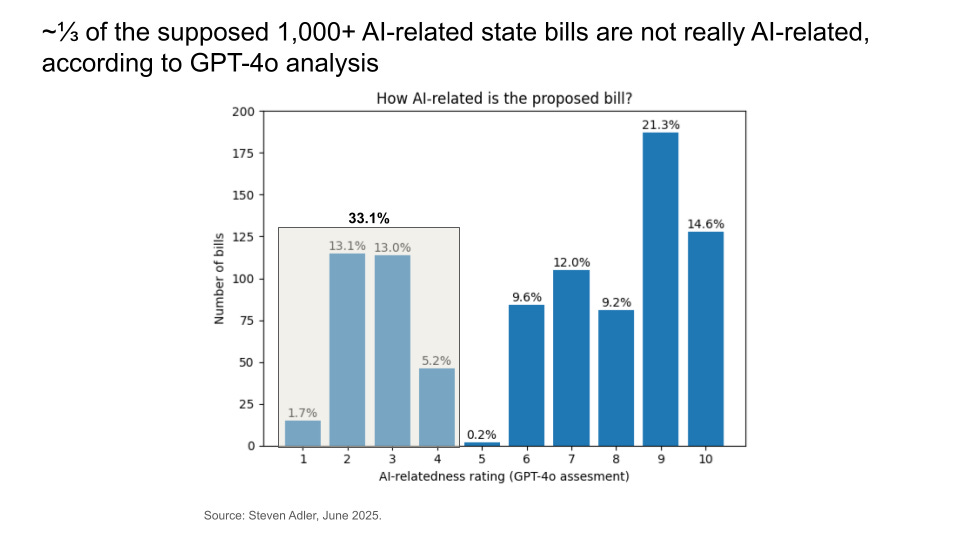

I am but a humble army of one, and so for this I enlist GPT-4o as my assistant: asking it to individually score each bill on how AI-related it is, ranging from 1 to 10 (most), graded on an absolute basis (not relative to the other bills).

Pretty similar to what I find above from keyword analysis, roughly one-third of the bills aren’t really related to AI at all (scores between 1/10 to 4/10), according to GPT-4o.6

Here’s an example of a bill that GPT-4o classifies as moderately AI-related (6/10), South Carolina’s House Bill 3796. In what way does this bill relate to AI?

Specifically, this bill prohibits the government from “recognizing legal personhood in certain items,” like the potential legal personhood of artificial intelligence, sure, but also a prohibition on recognizing the legal personhood of a body of water, atmospheric gases, or an astronomical object. Is that really an AI bill that justifies a state moratorium? (Note that this bill does mention “artificial intelligence” twice, and so it is already ahead of 40% of bills on the AI-relatedness keyword analysis.)

So, some of the supposed state bills aren’t really about AI, but some of course are. That’s useful to know. (You can access my scrape of all the relevant state bills here.)

Let’s go further: How often are these AI bills onerous, such that they might create a messy patchwork of regulations that would truly hamper advanced AI development?

Roughly 90% of the true AI bills still don’t impose specific requirements on AI developers

There are many types of AI-related bills that are not the “patchwork regulation” boogeyman being trotted out by critics.

For instance, some AI-related state bills are supportive of artificial intelligence, and so definitely shouldn’t be counted as supposedly hobbling innovation.

Here’s an example, North Carolina’s Senate Bill 619: It is AI-related, sure, in that it allows public schools to contract with Khan Academy for AI-assisted lesson plan development and even provides them funding to do so. But this bill is not at all a case of hobbling via patchwork regulation.

Here is another very common type of bill, which GPT-4o classifies as 9/10 on AI-relatedness; Alaska’s House Concurrent Resolution No. 3, which “[e]stablish[es] the Joint Legislative Task Force on Artificial Intelligence” to study artificial intelligence for the state and to “provide a comprehensive report” related to future legislative decisions.

Those are a few specific examples. More generally, the relevant question to ask of states’ AI-related bills is how onerous and specific they are, in terms of requirements on the private sector.7

For this question, I again turn to my assistant, GPT-4o, to grade the actually-AI-related bills based on how much they impose specific requirements on developers of artificial intelligence, like OpenAI and Anthropic.

The result is that, overwhelmingly, these bills do not seem to be the type feared; these bills don’t impose onerous requirements on the developers of AI systems.8

There are of course many limits of this analysis, but if critics want to make sure that contradictory requirements of state bills are addressed, it would be helpful to point these out specifically, rather than implying them through headline numbers of bills. Many of these bills, it seems, are not in the ballpark of creating a regulatory patchwork.

80% of state bills don’t pass, and so citing bill-count is misleading anyway

Beyond AI, state legislatures propose many bills for all sorts of things. For instance, in 2023 state legislatures introduced roughly 120,000 bills; the headline figures for state bills just tend to be very high.9 Even a true 1,000 AI-related bills would not be a very large percentage of state regulatory activity.

Still, only roughly 20% or so of state bills will pass,10 and so you need to apply a big haircut right off the bat to any bill-count.

Indeed, if you look to sources of what AI-related bills have actually been enacted in a given year (rather than merely proposed), you start to get substantially smaller numbers—especially if you also narrow in by “bills that matter for the private sector,” as I’ve tried to do above.

The best source I’ve found for this analysis is the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP), which has a tracker of AI governance-related bills.11 In 2024, they judged that four relevant bills were signed into law, with roughly 30 other significant bills considered but which did not become law. In 2025, they are tracking roughly 40 AI-related state bills (which again will mostly not pass into law) with the potential to be significant.12 These figures seem much more grounded than the oft-cited 1,000+ figure.

My takeaways

It would be helpful if critics of state AI regulation would be more specific about any contradictions or issues with particular state bills. If there are actual conflicts in these bills, I’d like people to be able to address the issues in the most specific form possible. More generally though, we should be cognizant of the costs of regulation, even if bills do not contradict each other: Regulation for its own sake would be bad, and there’s of course a cost to comply with even well-justified laws.13

The claim about “1,000+ AI-related bills” is clearly too broad to be useful and is not substantiated by the data. Often these bills are not really AI-related, and even when they are, they still A) might not impose requirements on AI companies, B) might not pass and become law, and C) might not conflict with any other passed laws.

It is reasonable to want federal AI regulation and to want this to take priority over state legislation. There is value in uniformity and universalness of regulation. (Though there is also value in the freedom to experiment across states.) For certain issues, like national security, the federal government might have more expertise, and we might not want to fragment expertise across jurisdictions. If I had my choice, I’d also favor strong federal AI regulation over many states’ approaches.

A desire to prioritize federal regulation does not necessarily support prohibiting state regulation. States can have an important role to play in filling the void when the federal government doesn’t pass important laws. Likewise, states can provide useful experiments to help establish what laws are workable and useful at a federal level. Because it now seems like states will be permitted to regulate AI after all, this is a silver lining that can set us up for strong eventual federal policy.

Acknowledgements: The views expressed here are my own and do not imply endorsement by any other party. All of my writing and analysis is based solely on publicly available information.

If you enjoyed the article, please share it around; I’d appreciate it a lot. If you would like to suggest a possible topic or otherwise connect with me, please get in touch here.

Ten years is essentially an eternity in terms of AI change and progress, and so this would be a very big deal.

The Congressional debate has gone back and forth on whether certain forms of state AI regulation would be exempt from the moratorium, such as regulation regarding deepfakes and child safety.

As of today, it seems like the Senate has voted to remove the AI regulation moratorium from the “Big Beautiful Bill,” and so the debates may now finally be settled.

In 2024, the IAPP (a professional association focused on “privacy, AI governance, and digital responsibility”) counted four significant AI governance laws enacted by states. I talk about this analysis more within the article’s body. In 2025, the IAPP is tracking roughly 40 proposed bills that have the potential to become significant laws if enacted, which roughly lines up with my own analysis. You should of course take these figures and my own analysis with a grain of salt, but I find them to be more thorough and precise than the oft-repeated 1,000+ claim.

When people have made the claim about the supposed 1,000+ AI-related state bills, they have almost always done so without citing a primary source, and so I have made my best attempt at determining what information people are relying upon.

The best primary source I’ve seen comes from the National Conference of State Legislatures. They have assembled a useful resource: 1,033 pieces of state legislation proposed in 2025 (up through late April) that they describe as AI-related (though not necessarily AI-related in the moratorium sense; that is an interpretation being applied by others, not coming from the NCSL directly).

There are two other sources I looked at closely: One is this spreadsheet of 300 or so laws that might be affected by the moratorium (related press release), though because this doesn’t connect to the 1,000+ claim, I set it aside as a useful-but-different resource. A second is multistate.ai’s maps of AI legislation by state, though the underlying data are not public: I suspect that it draws upon largely the same raw data as NCSL, though I cannot confirm this, and I notice that the numbers of bills quoted on multistate.ai are slightly bigger than in the NCSL database. I read this as MultiState perhaps using a looser definition of AI-relatedness for their criteria. I conclude from this that if we assess the NCSL bills as not being AI-related in the moratorium-relevant sense, probably MultiState’s set of bills is even less moratorium-relevant.

Note that the NCSL webpage describes their set of bills as “key legislation related to AI issues generally.” The NCSL notes that legislation related solely to specific AI technologies, such as facial recognition, deepfakes, or autonomous vehicles, is tracked separately, though I do see examples of these pieces of legislation among this list, and so I believe this list includes both general and specific pieces of legislation. For instance, using their search tool for “deepfake” identifies 18 bills among this list.

A pretty common type of bill deals with “algorithmic systems” for purposes like setting an apartment’s rent. This technology is quite different from the types of AI we think about regarding competition with China, the major AI developers like OpenAI, etc. In my analysis, I also looked for related keywords like “machine learning” and “neural networks” as well, in addition to using GPT-4o for general conceptual analysis.

Specifically, among Alabama’s 5.5 billion dollar allocation for public education in general, there is a $125K grant to Alabama A&M University for programs related to “Artificial Intelligence, Cybersecurity and STEM Enhancements,” which is 0.002% of the educational funding provided.

My methodology is straightforward given the time constraints of the Congressional debate: Initially I probed each bill with GPT-4o multiple times, but I did not observe much variance. Usually the bill was assessed as the same rating multiple times, or differed by just one-out-of-ten. Accordingly, I simplified the methodology to one assessment per bill with the model. You should of course take this analysis with a grain of salt: I am an army of one, and so I don’t have the capacity to read through each bill extensively, certainly not on the timeframe of the claims being made about the supposed 1,000+ bills. For thoroughness, I have spot-checked the methodology and results; the instances I’ve looked at by hand all match my expectations. Still, I’d certainly expect some slight variations in scoring if I had significantly more time and resourcing. I expect to loop back and open-source my code/analysis so that others can replicate and build upon it if they wish; for now, I have open-sourced the scrape of the bills themselves here.

Really, the question should go further: not only whether the requirements are onerous and specific, but whether they contradict across states.

When I sense-check this finding by tallying the score for a bill that does actually entail changing the behavior of frontier AI developers—New York’s RAISE Act—GPT-4o (correctly, in my opinion) assesses that bill as imposing specific requirements. Still, even this doesn’t establish that the requirements would be contradictory with requirements of any other law.)

This statistic is from LexisNexis, which also notes that the rate of bill passage can vary substantially by state, and so the most precise statistic would account for which states each bill is proposed within.

Here is their 2024 tracker and their 2025 tracker. Here is how IAPP describes which bills are included or excluded: “This chart is curated to spotlight legislation directly impacting private sector organizations, excluding government-only bills. While such standards influence AI policy, they generally do not impose immediate obligations on private sector organizations. Sectoral AI activities, despite their significance, are also omitted from the chart due to their limited scope.”

These figures are consistent with my own analysis: It seems much more defensible that there are roughly 40 AI-related state bills that actually matter for AI development, as opposed to the 1,000+ number that is often implied. Note that this count still would not substantiate either that the requirements of such bills would be onerous, unjustified, or contradictory with one another.

These costs can hit especially hard for smaller companies, which might struggle to track the different requirements and stay on top of them.

Excited to dig into this timely analysis! (rubbing hands gleefully)

TY! They deleted the "no AI state laws for five years" from the big bill :-)